The Story of Antibiotic Discovery: Part 1

How an accidental discovery in an untidy lab changed the world

A rather grumpy looking Alexander Fleming… Not all scientists look this miserable, we promise!

It was a cold September evening in London, 1928.

Dr Alexander Fleming was returning from a holiday in Scotland and, like most research scientists, returned to find a VERY messy lab bench, having not tidied before he left — scientists like to call mess ‘organised chaos’.

Dr Alexander Fleming was born in 1881, and studied medicine at St Mary’s Medical School, London. Once qualified, he began his career in research in 1906. He quickly became interested in the science of infection, the bacteria that cause the infections, and in antiseptic substances that were toxic to them.

In 1928, Fleming was working with one such bacterium, called Staphylococcus (pronounced “Staff-ill-oh-cock-us”). Bacteria can be grown on ‘agar plates’, which are basically solidified jelly jampacked full of nutrients and bacteria food.

Fleming had left agar plates with Staphylococcus growth on his lab bench.

When he returned from his holiday, he found an agar plate of Staphylococcus open near a window. The plate had become contaminated, and on it grew a fungus mould — just like on food if you leave it out of the fridge for days!

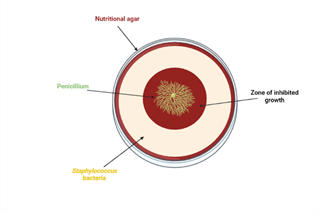

Interestingly, Fleming observed that the Staphylococcus growing close to the mould were being killed, leaving a clear zone of no growth, or what we now would call a ‘zone of inhibition’.

Take a look at the picture below — this is similar to what Fleming would have seen.

Like any good scientist, Fleming was intrigued. It was clear that the mould was doing, or making something, that was killing off the nearby bacteria. So he decided to investigate further!

Firstly, he identified the mould as a fungal species called Penicillium (pronounced “Penny-cill-ee-um”). He found that this fungus had the same effect at killing a whole host of bacteria that caused some really nasty diseases, including diphtheria, gonorrhoea, meningitis, pneumonia and scarlet fever!

The next question was HOW the Penicillium was killing the bacteria?

Fleming discovered that it wasn’t the mould itself that killed the bacteria, but a fungal secretion. Penicillium was releasing a toxic ‘juice’ that would stop bacteria growing — that’s why Fleming saw the ‘zone of inhibition’ around the Penicillium. This fungal juice Fleming called penicillin — what would become our very first antibiotic.

Fleming published his exciting findings in a scientific paper to, in all honesty, not a whole lot of attention at first. Sadly Fleming had neither the ability, nor the money, to take his research further. As such, his work slowed, as it was impossible for him to isolate as much penicillin juice as he needed.

Eventually, his work was picked up by two fellow scientists, Ernst Chain and Howard Florey, but that is a story for Part 2, which will be coming soon!

So you see, science is about hard work, intrigue and investigation, but often it’s also just about being lucky! As Fleming himself said: “One sometimes find what one is not looking for. When I woke up after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionise all medicine by discovering the world’s first bacteria killer. But I guess that was exactly I did.”

For Fleming, being rather messy and untidy actually led to the most important discovery in medicine: antibiotics! Remember that next time your parents nag you to clean your bedroom 😉 (but don’t tell them we told you)!