Smallpox: The Disease That Made History

From the biggest killer in the world to the first infectious disease ever to be eradicated

Watercolour illustration from a Japanese manuscript entitled Toshin seiyo [The essentials of smallpox], c. 1720.

Smallpox was a highly contagious and often deadly disease caused by the variola virus. Smallpox was transmitted by contact with infected patients, typically through the air by droplets that escape when an infected person coughed, sneezed or talked.

The first symptoms of smallpox usually took around two weeks to appear. The disease then started by a sudden onset of fever, headache, tiredness, pain and vomiting. A bit like coming down with the flu. But a few days later, red spots would start to appear on face, hands and forearms, and later on the rest of the body. Many of these lesions would develop into pus-filled blisters. Scabs would begin to form a week later and eventually fell off, leaving deep scars on the skin. Lesions and sores also developed inside the nose and mouth.

Smallpox was so widespread in Europe and Asia that most people would become infected at some point during their lifetimes. And on average, 3 out of every 10 people who got it would die. People who survived usually kept scars, which could be severe and disfiguring, and many went blind as a result of the infection.

There was no cure or treatment for smallpox. And there still is none.

One of the worst killers in human history

The origin of smallpox is unknown.

The earliest evidence for the disease comes from the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses V, who died in 1157 B.C., and whose mummified remains show smallpox-like rashes on the skin.

In Europe, smallpox is estimated to have claimed 60 million lives in the 18th century alone. In the 20th century, smallpox killed some 300 million people globally.

After wreaking havoc mainly in Europe and Asia over three millennia, smallpox was particularly devastating in populations that had never come into contact with the virus before and therefore possessed no natural immunity against the disease.

Smallpox thus contributed to the decline of the ancient empires in Central and South America, following the European conquerors after Christopher Columbus’s journeys to the New World. At the beginning of the 16th century, more than three million Aztecs are thought to have succumbed to smallpox in what is now Mexico. Likewise, smallpox wiped out much of the Inca population in what we know today as Peru.

A century later, smallpox (together with other ‘European’ diseases like measles, plague and chickenpox) severely decimated the indigenous people in North America. And after the arrival of the first Europeans in Australia in the 18th century, a large proportion of the Aboriginal Australians were killed by smallpox.

Arguably, no other infectious disease has had a greater impact on the course of world history.

The first clinical trial and the Princess of Wales

Lady Mary Pierrepont, Lady Mary Wortley-Montagu, after Jonathan Richardson the younger, after 1719 | Middlethrope Hall | National Trust Images

One of the first methods for controlling smallpox was ‘variolation’, a practice named after the variola virus. During variolation, people who had never had smallpox were exposed to material from smallpox sores of infected patients, by scratching the material into their arm or inhaling it through the nose.

After variolation, treated people usually developed smallpox symptoms - in many cases in a milder form but some people were also killed by the treatment! But still, fewer people died from variolation itself than if they had contracted smallpox so on balance it probably was worth the risk.

Would you have taken it? Or given it to your children?

Variolation seems to have been practiced in China for hundreds of years and was also known in India, the Middle East and parts of Africa by the beginning of the 18th century.

Lady Mary Wortley-Montagu, the wife of the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (now Turkey), learned about variolation while living in Istanbul and decided to introduce this life-saving method in Britain.

Her own brother had died of smallpox, and she herself had been lucky enough to recover from severe disease at the age of 26 – yet she had been left with a disfigured face from the scars.

In 1718 and 1721, she tested the effect of variolation on her two children, most likely saving their lives. Fun fact: Lady Mary’s daughter would later have a son who would become the 1st Marquess of Bute and owner of Cardiff Castle.

Then, in order to convince King George I of the safety of variolation, Lady Mary was granted access to a group of six prisoners awaiting their execution. They had been promised freedom if they survived the experimental treatment. In fact, they all did well and were released from prison. A second study was run on eleven orphan children.

These were Europe’s first clinical trials, as we would call them today – tests of a new drug or medical procedure on groups of humans to see if it is safe and effective. However, it is not clear that the participants truly volunteered for these experiments, and whether they had been made aware of the risks of the treatment. In the modern sense, Lady Mary’s studies would be considered ‘unethical’.

Ultimately, the king allowed the Princess of Wales to get two of her daughters (the king’s granddaughters) treated, encouraged by the success of Lady Mary’s studies. And with the associated publicity of treating the Royal family, the practice began spreading, and others followed with improving the practice further.

The slave and the minister

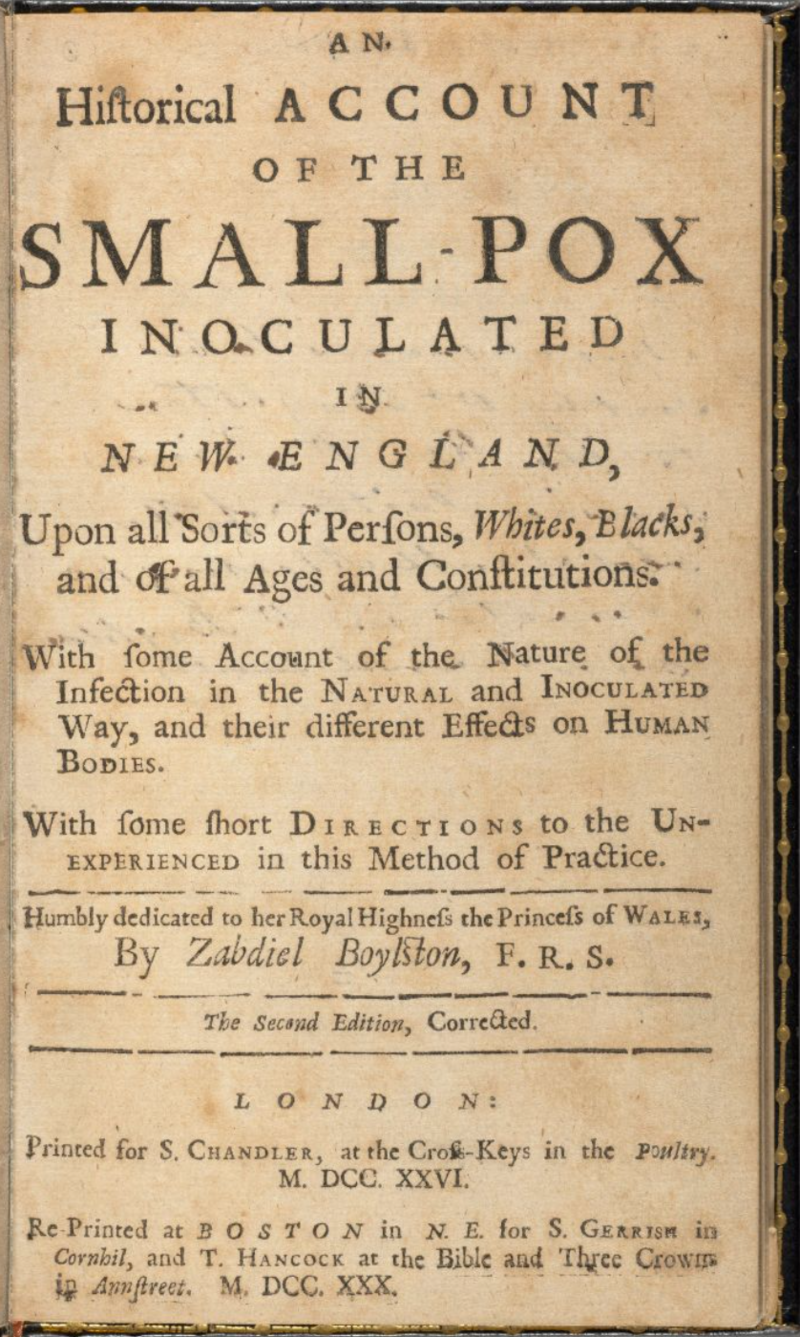

“An historical account of the small-pox inoculated in New England”

by Zabdiel Boylston (1726)

In parallel to Lady Mary’s work in England, an enslaved man from Africa would save Boston in New England from smallpox. He had been sold to the influential minister Cotton Mather in 1706 and named “Onesimus”; the slave’s real name, his country of origin and his date of birth remain unknown.

Onesimus described to Mather the practice of variolation as it was performed by many societies in sub-Saharan Africa, and as proof showed him the mark the variolation had left on his skin.

When Boston was hit especially hard by the smallpox in 1721, with cargo ships from Europe repeatedly bringing the disease with them, Mather tried to convince the local authorities to adopt the procedure to protect the local citizens. However, he was met with strong skepticism by doctors and officials, and ridiculed publicly for relying on the (what they considered untrustworthy) testimony of a slave. At the core of Boston’s resistance to inoculation was a heavy racial bias, combined with a strong religious believe that treating healthy people would directly interfere with God’s will of sending the smallpox epidemic.

Nonetheless, a physician called Zabdiel Boylston decided to take the risk and carry out the method Onesimus described, first on Boylston’s own 6-year-old son (unaware that in England Lady Mary similarly tried out the procedure first on her own children), and then on two of his slaves. He went on to treat around 280 people, and when the smallpox hit, only six of the inoculated people would die. This relatively low death rate of 2.2% was in striking contrast to the high mortality in the untreated rest of the population, where 14.3% of all smallpox patients died. The clear difference strongly supported the protective effect of the procedure, and as a result it was adopted more widely cross New England.

Recognition for Onesimus’s contribution to medical science came in 2016, when he was placed among the “100 Best Bostonians of All Time” by Boston magazine.

The milkmaid and the gardener’s son

Dr Eward Jenner performing his first vaccination, 1796. Oil painting by Ernest Board.

The basis for real vaccination began in 1796 when the English doctor Edward Jenner noticed that milkmaids who had gotten cowpox, a relatively mild skin disease caught from infected cows, were apparently protected from catching smallpox.

Jenner knew of course about variolation, and he postulated that experimental exposure to the safer cowpox could be used to protect against smallpox.

To test his theory, Dr Jenner took material from a cowpox sore on the hand of the milkmaid Sarah Nelmes and inoculated it into the arm of James Phipps, the 9-year-old son of Jenner’s gardener. Months later, Jenner exposed Phipps several times to the variola virus. But James never developed smallpox.

Yet another unethical experiment! What would have happened if the boy had fallen ill or even died from smallpox? Would you have agreed to be exposed to a deadly disease? Or have your own child treated in this way?

Further successful experiments with more people followed, and in 1801 Jenner published his findings, expressing his hope that ‘the annihilation of the smallpox, the most dreadful scourge of the human species, must be the final result of this practice.’

Jenner also coined the terms ‘vaccine’ for his discovery, based on the Latin word for cow (vacca).

The rest is history. Jenner achieved all the fame. Lady Mary’s efforts, which laid the foundation for his work, fell into relative obscurity.

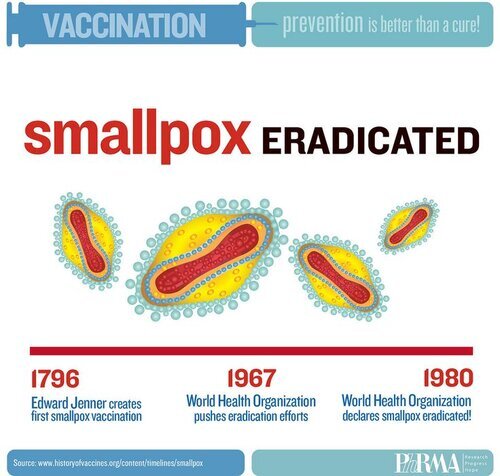

The first infectious disease to be eradicated

With time, vaccination became widely accepted and gradually replaced the crude practice of variolation.

Curiously, a recent analysis of a 100-year-old sample of smallpox vaccine showed that it was in fact 99.7% similar to horsepox virus, not cowpox! At some point in history someone must have used material isolated from horses instead of cows but it is impossible to trace back now why and when this happened. Which means the word ‘vaccination’ is actually wrong, and we should rather call it ‘equination’, after the Latin word for horse (equus)…

With increasing efforts to vaccinate people, and also with general improvements to diagnose and isolate infected patients, smallpox numbers began to decline. And by the 1950s, the disease had disappeared in North America and Europe.

In 1959, the World Health Organisation (WHO) started a plan to rid the whole world of smallpox and set up an effective case surveillance system to be able to monitor disease outbreaks, and organised a global mass vaccination campaign. A bit like the current efforts to immunise everyone against Covid-19.

And so one day in 1977, Ali Maow Maalin, a hospital cook in the town of Merca in Somalia, happened to come in contact with two local patients who had contracted smallpox. 10 days later, he himself developed a fever - and was wrongly diagnosed first with malaria, then chickenpox. Smallpox was already a pretty rare disease at that time, and many doctors would have missed the typical signs! But specialist staff finally diagnosed him correctly with smallpox and isolated him so that he would not pass the disease to anyone else. Ali made a full recovery.

He was the last person in the world to have naturally acquired smallpox.

Then in 1978, a woman called Janet Parker who worked as a medical photographer at the University of Birmingham, one floor above the Medical Microbiology Department, suddenly became ill one day. She developed a rash a few days later but was not diagnosed with smallpox for another week. Sadly, she died on 11th September 1978.

An investigation later suggested that Janet had probably been infected either via the ventilation of the building she was working in, or by direct contact with the virus while visiting the microbiology laboratory, where staff and students happened to conduct smallpox research.

Janet was the last person ever to die of smallpox.

After Ali’s recovery and Janet’s death no further cases of smallpox occurred anywhere in the world. In 1980, almost two centuries after Edward Jenner’s ground-breaking work, the WHO declared the world officially free of smallpox.

Smallpox was the first infectious disease to have been wiped off from history. To date, it remains the only human infection to have been eradicated.

Let’s see if we can achieve the same with polio, measles and Covid-19!

Want to learn more? Check out our timeline of infectious diseases, treatments and vaccines through history!

This text was compiled in part using the following resources:

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/smallpox

https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html

https://time.com/5542895/mary-montagu-smallpox/

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/smallpox/symptoms-causes/syc-20353027

https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/blog/onesimus-smallpox-boston-cotton-mather

![Watercolour illustration from a Japanese manuscript entitled Toshin seiyo [The essentials of smallpox], c. 1720.Wellcome Collection gallery](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60508655a0295656f4b304d5/0b68d05a-1e6d-439f-ab9c-c201218d3c0b/1200px-Smallpox_illustration%2C_Japanese_manuscript%2C_c._1720_Wellcome_L0074642.jpg)